C_Methods

In this project, the already tested DBGI methodology will be applied on trees. They differ from precedently sampled plants as they bear lignified organs (bark, branches, pinecones, ...) which cannot be pulverised by the spherical metal beads used in the standard protocol. However, this nuisance might be overcome by using discoid beads instead.

So far, each sample wasn't considered as being linked to a peculiar specimen. They were considered independant from each other, even tho they came from the very same individual. As the samples were mostly leaves. This wasn't a big issue for no more than a single sample was taken from the same indivudal.

In this regard, trees offer an interesting challenge and an opportunity to further develop the EMI tools as they are perennial, and don't present all of their organs at the same time. Therefore, being able to attach samples to a specific individual could allow to come back to collect missing organs or study the modifications of the metabolome through the year(s). To achieve this, Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs) transcribed in QR-codes were generated and attached to the specimen's panel. For now, ticks can be made at the back of the code to mark and follow the progression of the sampling on the specimen (Figure C-02).

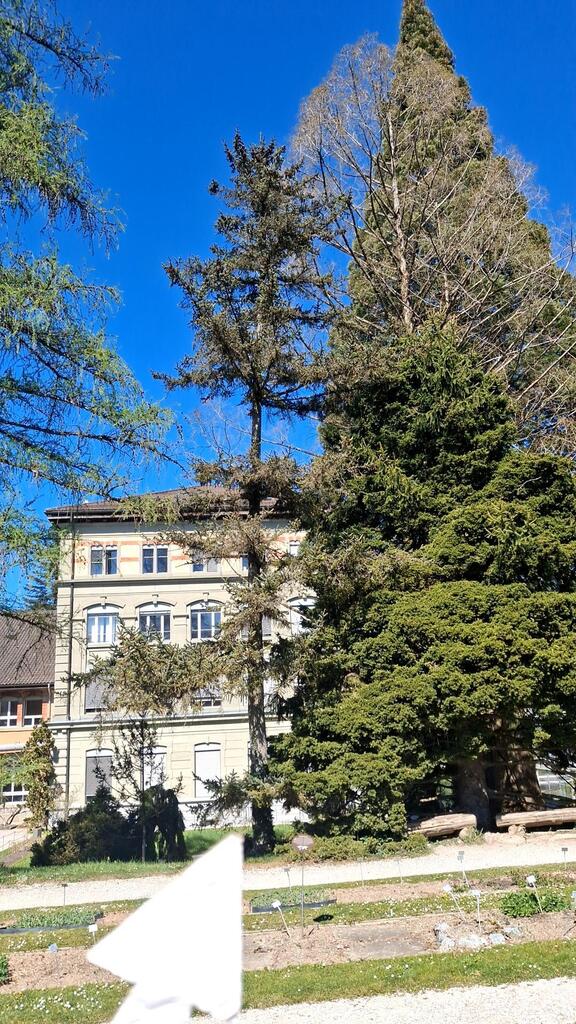

Approximately 130 trees of the botanical garden have been sampled for this bachelor's work. They are scattered all over the garden, with a greater concentration in the arboretum, on the border of the system, and near the outside fences (Figure C-03). The JBUF is home to local species (Picea abies) aswell as tropical ones (Persea americana).

This work might show a strong bias toward gymnosperms as they tended to show a greater number of organs early in the year (this project took place from February to May).

C_1 Sampling

The classical DBGI methodology was applied to collect different organs. The main difference being the use of a standard secateurs, and a telescopic one to cut branches off. For each sample, the geographical position of the specimen is marked down on a map of the JBUF using the QField app. At least 5 pictures must be taken for each sample:

1) The whole specimen (Figure C-04).

2) The identification panel with the UUID QR-code (Figure C-05).

3) The identification panel with the UUID QR-code and the number of the sample (Figure C-06).

4) Details of the plant (Figure C-07).

5) The sampled zone indicated by the cutter (Figure C-08).

6) Additional picture, if judged necessary.

See an exemple for Picea jezoensis. You can find its associatied observation on iNaturalist.

The different pictures and the geolocalisation of the sampled plants, are then imported on iNaturalist to confirm the belonging of the specimen to a species. This, allows the collectors to harvest large quantities of plant matter without having to be trained botanists themselves, speeding up the progression of the project and allowing for interesting citizen science initiatives.

The organ must be separated from the parent organism. After the cut, the organ is wrapped in a brown coffee filter, and shoved in a falcon tube closed with a perforated cap. Each tube is pre-labeled with a unique number and QR-code which allows to identify and track the sample through its preparation and storage. The tubes are then temporarily submerged in liquid nitrogen. If they can't be freeze-dryed immediatelly, all tubes are stored in a -70°C freezer.

C_2. Extraction

The freeze-drying process needs to be at least 72 hours long to make sure the samples are absolutely dry. Directly after the freeze-drying process, all the perforated caps need to be switched with standard, disinfected, non-perforated caps to avoid contamination from the environment. The falcon tubes are then scanned and stored in a labeled rack. From now on, the tubes will be stored in said racks to allow easy access to the samples if need be.

The first step of the extraction process is the weighing. 50 mg needs to be weighted and inserted in a 2ml Eppendorf tube with a rounded bottom. An error up to ±5% (±2.5 milligrams) is accepted. Three 4mm metal beads, or three disc beads if the sample is a needle, lignified, or deemed to hard, are added.

The Eppendorf tubes then go in the MM40 Retsch machine (shaker) for 2.5 minutes at 25Hz for standard beads, and 5 minutes at 25Hz for the discoid beads to grind the dried plant matter into a powder. Then, 1,5ml of the DBGI extraction solution is added. Said solution is made of a mix of 80% methanol, 20% distilled water, and 0,1% formic acid. The newly rehydrated samples go back in the Retsch machine for a second round with the same settings depending on their content.

The tubes are then centrifugated for 2 minutes at 13'000 RPM to split the supernatant from the plant deposit which precipitates.

Afterward, as much of the supernatant (usually 1,4ml) is carefully collected and pipetted in a glass vial (2 milliliters) with a hermetically sealed cap (Figure C-08). Floating particles need to be avoided for they tend to clogg the LC-MS. The vial needs to be labelled and associated to a container, ensuring the continued tracking of the sample from the garden to the freezer. The vials' container is then stored in a -70 °C freezer, and is ready for LC-MS and analysis.

C_3. Analysis

120 microliters of the extracted liquid is pipetted from the hermetically sealed vial to a new vial containing an insert to create an aliquot (Figure C-09). The new vials are closed with a slitted cap which allows the machine to access the solution. These aliquots are the final step needed before analysing the samples through untargeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS). The spectra produced by the machine are then analysed by specialised software (see chapter D_Metabolomic Analysis).

C_4. Sample Tracking & UUID

One of the key aspect of the DBGI is establishing and preserving linkage between the field and the database. Therefore, a reliable sample tracking system is necessary to keep track of the numerous samples for the entirety of their processing. As soon as a sample has been collected, a unique code is assigned to it. It will follow it through each stage of preparation, from extraction to storage by being reported on all containers the sample will go through. This allows to efficiently link the data, and the metadata of the sample into the database.

To go further in the labelling process, this Bachelor's project focuses on the introduction of Universally Unique IDentifiers (UUIDs), also known as Globally Unique IDentifier (GUIDs) in the established workflow. UUIDs are 128-bit labels used to uniquely identify objects in computer systems. They are excellent for the purpose of the EMI, as they don't need central authority, and can be generated in the field, even in the absence of internet connection. Attributing the UUIDs to to sampled individuals adds an extra layer of information by giving it its own individuality. This is interesting as each individual differs in state and as such, in metabolomic contents. It allows the DBGI to be more precise in its metadata assignation.

One important point to keep in mind is that other alternatives to UUIDs such as LSID, URN, HTTP URI, DOI, IGSN, ... exist and are used in different biocollections. The biodiversity community hasn't decided on a single method to use as of yet. No specific method prevails on the others (Guralnik et al., 2015), whith their own advantages and drawbacks.

As such, the method used by the DBGI to track individuals might change as time goes on.

Backlinks